In 2014, Dr Isamu Akasaki was co-awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work leading to the "invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes which has enabled bright and energy-saving white light sources". His breakthrough came after countless setbacks, as he persisted in trying to develop a blue light-emitting diode (LED) using gallium nitride (GaN), a concept that most other researchers had concluded -- following years of failed experimentation -- was unworthy of further pursuit. In fact, Dr Akasaki had been described as a "persistent" researcher in the news release announcing him as the recipient of the 2011 IEEE Edison Medal.

A 1952 graduate of Kyoto University's Faculty of Science, Dr Akasaki still professes deep affection for his alma mater and for the city of Kyoto, and he often mentions the University's culture of encouraging independent work as having helped shape his professional attitude, enabling him to persevere in the face of adversity. The following interview explores the background of this dogged researcher, with a focus on his experiences as a Kyoto University student.

A boy with a longing for Kyoto

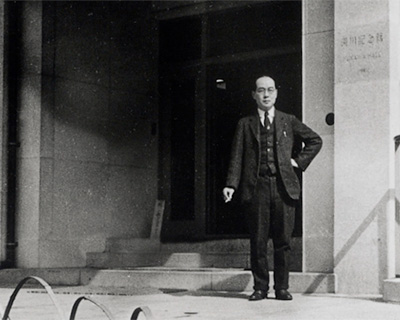

Dr Isamu Akasaki

Isamu Akasaki was born in what was then the town of Chiran (now part of Minamikyushu City), Kagoshima Prefecture, in 1929. He grew up in Kagoshima City but, together with his family, made a few annual trips to his ancestral hometown of Chiran. It was during one of those visits that a yearning for Kyoto first arose in Dr Akasaki's heart.

We would spend summer and New Year's holidays in Chiran, our ancestral hometown. The town included a district of bukeyashiki, or samurai mansions. My relatives would say to me, "Those mansions have gardens that are modeled on those in Kyoto, and they were built by experts brought in from there". The word, "Kyoto", somehow got stuck in my mind.

Back in Kagoshima City -- away from Chiran and its bukeyashiki -- I still thought of Kyoto, albeit only occasionally. Then, I started at the local Seventh Higher School (precursor to Kagoshima University) and found myself sharing a dormitory room with a boy from Kyoto. He had many stories to share about his hometown, resulting in my childhood memories of Chiran coming back to me and my longing for Kyoto growing ever more intense.

Still attached to Kyoto

After graduating from Kyoto University, I went to work in Kobe and Tokyo but regularly returned to Kyoto to keep up with old friends and savor the city's distinctive atmosphere. The late Dr Minoru Matsuo, Nagoya University's 11th President and a graduate of the Kyoto University Faculty of Engineering, used to say, "I make a point of returning to Kyoto every other week, if not more frequently, regardless of whether or not I have any work to do there". I think I understand how he must have felt. Actually, I returned to Kyoto six or seven years ago, when I had recovered sufficiently from major surgery to be able to travel. One of the things I did on that trip was to wander aimlessly around the University. Somewhere around Hyakumanben, I came upon an old coffee shop, one in which I had spent many hours with my student friends. Something that strikes me about Kyoto University is that it is inseparable from its surroundings -- in fact, it seems to form an indivisible whole with the city of Kyoto. I wonder if this level of university-city connection is something peculiar to Kyoto. There is a famous student song, "Alt Heidelberg". I have heard it said that this song, with its references to Heidelberg University and the Neckar, could just as easily be about Kyoto University and the Kamo River. I don't know of any other university that has an equivalent of these rivers.

Day One lecture and a vow

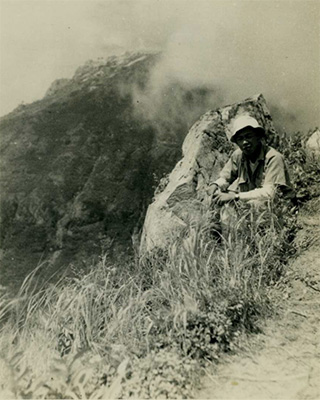

Isamu Akasaki (far left) on a tour of temples and shrines with his friends (Mt Daimonji, 1950)

Isamu Akasaki was accepted into Kyoto University's Faculty of Science in 1949, after passing a highly competitive entrance examination that more than 90 percent of the applicants failed. On his first day, he would receive a lecture on what it meant to be a KU student.

Unlike under today's system, university students of our time were each supposed to join a laboratory upon enrollment. The laboratory that I joined held a kind of cherry blossom-viewing welcome party for new members, following the University's entrance ceremony. During that party, we were strolling along the Philosopher's Walk, from the Ginkaku-ji temple to the Nanzen-ji temple, when one of the second- or third-year lab members said to me: "Universities are where you study, not where you are taught. Whatever you are seeking, you must reach out and grab it." These words still ring fresh in my ears. On later occasions, I would often hear people say that the role of a university was not to teach but to ensure that, by the time of graduation, its students would have developed the ability to deal with the unexpected and solve problems, and that Kyoto University was ready to do all it could to help us in this regard. Going back to the lecture from the senior lab member, it made me feel that I had been initiated as a university student. That was an unforgettable moment. From that day on, I kept those words to heart and never asked or expected to be spoon-fed anything. I was largely on my own, even when working on my graduation project. It was not just me; everyone I knew was more or less like that.

Later that same year, a momentous event would occur that would have a strong impact on Isamu Akasaki's future.

Dr Hideki Yukawa, another Kyoto University alumnus, was awarded the 1949 Nobel Prize in Physics. The news seemed to brighten up the whole of Japan, where people had all but forgotten about the prestigious award amid the nation's struggle to recover from the devastation of war. As far as I was concerned, Dr Yukawa and his achievement might as well have belonged to another dimension. However, walking along the plane tree-lined Konoe Street that day, I vowed to myself that I, too, would do something, however modest in scale, that no one had ever done before. It was 20 years later that I would learn about the blue LED, and, upon realizing that no one had ever succeeded in producing one, would recall that vow and decide to work on it.

Dr Hideki Yutaka in front of Yukawa Institute for Theoretical Physics, Kyoto University (circa 1954)

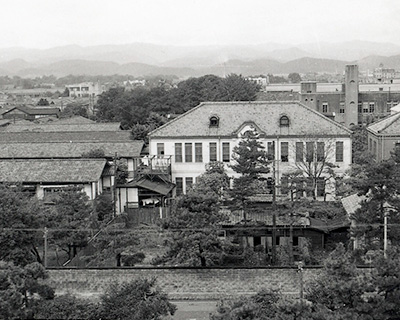

Faculty of Medicine Campus (fall 1957)

Post-war gloom and vibrant student life

Isamu Akasaki as a KU student (early 1950s)

Isamu Akasaki's student years began in 1949, the year in which Dr Yukawa received the Nobel Prize, and ended in 1952, when Japan signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty. What was the atmosphere like at Kyoto University during that period?

I found the atmosphere wonderful as I entered the University. It was in stark contrast to the gloom that had enveloped much of post-war Japan. For one thing, Kyoto itself had been spared air raids and the kind of devastation wrought on many other parts of the country. The university campus looked really impressive -- a radically different sight from the burned-out ruins to which my hometown had been reduced.

Another thing I noted was that students there were all highly motivated. Everyone around me was burning with a passion to play a part in Japan's recovery, even if they didn't always openly admit to it. About a year before my graduation, it was reported that Germany, another war-ravaged country, had achieved astonishing progress in its rebuilding process. Looking to Germany as a model, we all aspired, to varying degrees, to be part of Japan's industry-led growth.

Moving into Yoshida Ryo after a year of free accommodation

A little to the west of where the Kumano Ryo dormitory stands today, there used to be a traditional Kyoto-style mansion that belonged to an alumnus of the Seventh Higher School, who at that time served as vice-president of the local bar association. His household included several shosei (students given room and board in exchange for performing household chores), two KU students among them.

The lawyer invited me to live in his residence, and, it being a time of constant food shortages, I gratefully took up the offer. The problem was, he refused to accept any payment for the room and board, which made me feel guilty. Eventually, while talking with some of the older students I knew, I learned about a KU dormitory called Yoshida Ryo and decided to apply for a room there. It was, and still is, what is called a self-governed dormitory and, in order to be accepted into it, applicants had to pass an interview conducted by a group of residents. The competition to get into Yoshida Ryo was extremely fierce, back then, but I managed to pass the screening and became a resident.

As it happened, it was not my first experience of living in a dormitory; I had stayed in one -- another self-governed dormitory -- as a student at the Seventh Higher School. Actually, that was how I met some of my best friends at that school. It was the same with Kyoto University; my best friends were my fellow dormitory residents. It didn't matter which Faculty or Department they belonged to.

Yoshida Ryo in 1954

Yoshida Ryo -- something of a salon?

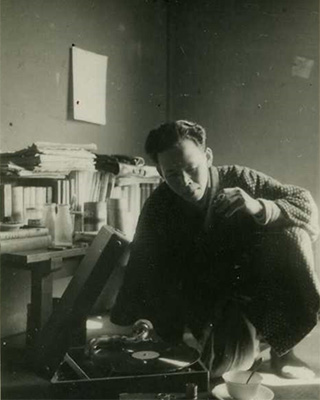

Yoshida Ryo consisted of old but impressive buildings. The rooms -- there was one for each resident -- were positioned a little higher than the floor level, a style that I found very attractive. It had a record room and an audio room -- which enabled me to listen to my favorite classical pieces to my heart's content -- as well as a tearoom. Yoshida Ryo served as something of a small library, too, as it subscribed to various newspapers for us all to read. Security was provided by two guards. The dormitory comprised three buildings -- north, middle, and south -- my room being in the middle one. I had a close friend living just a few rooms down the hall. We would talk late into the night in either of our rooms, comfortable in the knowledge that our beds were just a few minutes -- if not seconds -- away. The dormitory included an office staffed by three clerks who were available to cater to our various needs.

With my dormitory friends, I would frequently tour the Katsura and Shugaku-in Imperial Villas, which were usually closed to the public. However, we were allowed inside, thanks to arrangements made by our architecture teacher. We did so many things together; for instance, trekking over Mount Hiei to Lake Biwa. I am not sure if those activities had any positive influence on our study, though.

In the Northern Alps (summer 1951)

Isamu Akasaki listening to a record in his dormitory room (1952)

Beginnings of a persistent researcher

"Going alone through the wilderness" has become something of a catchphrase for Dr Akasaki. Can this attitude be traced to an experience or encounter he had as a KU student?

When I began conducting research on light-emitting diodes at Matsushita Research Institute Tokyo, which I had joined in 1964, I noted that none of us was working on a blue one. It turned out that a blue LED was something that everyone had attempted -- but failed -- to produce. That was when I realized that I had found my mission; I recalled the sense of awe I had felt 20 years earlier at the news of Dr Yukawa receiving the Nobel Prize, and the vow that I had made to do something unprecedented.

So, I embarked on a quest to make a blue LED a reality and, eventually, achieved a certain milestone. However, when I made a presentation on it at an international conference, no one responded to what I had to share with any enthusiasm. When, during a media interview held afterwards, I mentioned the failure of my presentation to generate much response, the reporter remarked, "I suppose no one else is doing what you are doing." True enough; none of the papers presented at the event concerned gallium nitride as a possible source of blue light, which was the topic of my research. "So, I am on my own," I thought to myself. At the same time, however, I kept telling myself that I would never give up what I was doing -- even if that meant having to work on my own.

The professor who instilled in Isamu Akasaki the importance of experimentation used the philosophical term, aufheben, to describe the process whereby theorization and experimentation follow and inspire each other, leading to new insights. Did he have an interest in philosophy or other fields of humanities despite being a science student?

I did, of course, have an interest in the humanities, as did most other students I knew. That was the case not only at the University but also at the Seventh Higher School, where we were advised to try and read at least 50 Iwanami Bunko books (small-format paperback books published by the Iwanami Shoten publishing company) a year. I was an avid reader and, in my second year at the Higher School, even considered majoring in literature at university. It was because of my love of mathematics, physics, and chemistry that I eventually decided to apply to the Faculty of Science.

At any rate, although I am not at all sure if my research has benefitted in any way from my reading habits, I am convinced that books do play a role in shaping how we live our lives. To read a book is to have a dialogue with oneself. So, it should be irrelevant whether or not it benefits one's work. The books that we read form the basis of our character and culture, whether we study science or humanities. That is my view.

In his lectures for high school students, Dr Akasaki always stresses that young people should think about their future from a global perspective, and he recommends following international news and getting out into the world.

In Kyoto, as well as in Nagoya, I have noticed that young people tend to be reluctant to live away from their parents, and the parents to live apart from their children. Those people just don't want to leave the comfort of the familiar. On countless occasions, I have urged young people to be more adventurous, reminding them that they have a whole wide world to explore. I also tell them that, even if they seem to be alone in what they are thinking at their school, there must be at least one other person -- somewhere in Kyoto, Japan, or the world -- who thinks exactly as they do. Likewise, to my students, I have always said that the world is bigger than they think. "Do not stay holed up in such a small country," I still say to young people. "Go for it -- go to New York, or wherever you want to go."

The invention of the blue LED, the achievement recognized with the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics, cannot be traced directly to any of Dr Akasaki's experiences at Kyoto University. Still, as the researcher himself mentions more than once in the above interview, the climate of freedom and the emphasis on self-study and self-learning that characterize the academic environment of his alma mater appear to have played roles in helping him to develop the ability and the willpower needed to forge his own path, which led to the invention.

Profile

Born in Kagoshima Prefecture in 1929, Dr Isamu Akasaki graduated from the Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University, in 1952. He went on to work as a researcher at Kobe Kogyo Corporation (now Fujitsu), Matsushita Research Institute Tokyo, Nagoya University, and Meijo University, achieving outstanding results in the fields of semiconductor crystal growth and photoelectronic device development. Of particular note is the work he did with gallium nitride (GaN), whose physical properties had long been considered impossible to control; he succeeded in growing high-quality epitaxial GaN films and controlling the conductivity of p- and n-type GaN, which led to the world's first GaN p-n junction blue/ultra-violet LED. He is also known for his contributions to the training of researchers in related fields, including compound semiconductor crystal growth, fundamental properties, and photoelectronic devices.

Dr Akasaki's work finally enabled production of blue light, which, as one of the three primary light colors, forms the basis of full-color display technology. In addition, the white LED, which is made by coating a blue LED with a phosphor material, is highly valued as an eco-friendly light source.

For these contributions, he was awarded the Person of Cultural Merit accolade in 2004 and the Order of Culture in 2011, before receiving the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2014 and the Honorary Degree of Doctor from Kyoto University in 2015.

(Interview conducted on 15 May 2015)