Kyoto, Japan -- In nature, ecosystems are tightly linked through the flow of organisms, detritus, and nutrients across boundaries arbitrarily imagined by humans. These systems are deeply in tune with seasonal changes, fostering a harmonious ebb and flow of resources.

Many of these connections remain poorly understood, especially the mechanisms responsible for maintaining biodiversity at the landscape level. One important example is the environmental drivers underlying variations in life-histories, or how organisms grow, survive, and reproduce in natural ecosystems. But as human activities ravage biodiversity on a global scale, elucidating the factors that cause variations in an organism's life-history is fundamental for understanding not only population persistence and adaptation to fluctuating environments, but also effective conservation and management.

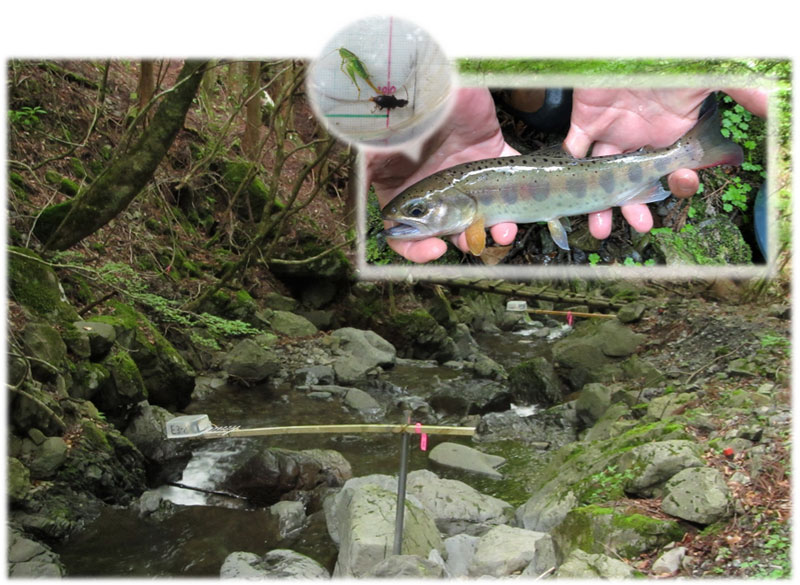

Motivated to shed light on these factors, a team of researchers at Kyoto University is studying how seasonally recurring resource subsidies affect life-histories. Via a large-scale field experiment in a temperate forest-stream ecosystem, they are testing whether the seasonal timing of terrestrial subsidies contributes to maintaining variations in life-history traits of red-spotted masu salmon, a common freshwater fish in Japan.

In this study, the team tracked the life-histories of more than 300 individuals of the fish, manipulating the seasonal timing and magnitude of terrestrial invertebrate resource subsidies. Their results reveal that seasonal linkage of ecosystems can mediate life-history variation of wild organisms through the transport of seasonally important prey resources.

"We were genuinely surprised to find that simply changing the timing and magnitude of subsidies led to different outcomes for consumer life-history and its variation," says corresponding author Rui Ueda. Specifically, life-history variation was highest when resource subsidies were supplied early in the organisms' growing period, and lower when the same amount of subsidies was supplied later or was not supplied at all.

The team also found that these factors caused variations in the relationship between growth and survival. When subsidies were limited, they observed a typical growth-survival trade-off, in which higher growth is associated with decreased survival due to resource limitations. However, this relationship became unclear -- or even reversed -- when subsidies were supplied. This may be due to changes in competition among individuals for food, as well as seasonal differences in resource allocation strategies.

Unfortunately, these results do not bode well for the world's ecosystems. Human-driven environmental changes are not only altering the amount of energy and nutrients that flow through ecosystems, but also disrupting seasonal timing, homogenizing the ways in which wild animals and plants grow and reproduce. Life-history diversity within a species aids adaptation to a changing world. A reduction in this variation can have dire consequences.

On a positive note, further research could help improve management of forests and streams as connected ecosystems. The research team is currently using long-term monitoring and mathematical modeling to test how changes in life-history variation can increase or decrease fish abundance.

【DOI】

https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.70114

Rui Ueda, Minoru Kanaiwa, Akira Terui, Gaku Takimoto, Takuya Sato (2025). Seasonal timing of ecosystem linkage mediates life-history variation in a salmonid fish population. Ecology, 106, 5, e70114.