Making sense of the Universe

An interview with

Kohei Ichikawa

PhD Candidate

Department of Astronomy

A meeting of astronomical minds

Launched in 2003, the East Asian Young Astronomers Meeting (EAYAM) brings together early-career astronomers from the East Asian region with the aim of promoting wider interaction and collaboration. Hosted by the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica (ASIAA) in Taipei from 9-12 February, EAYAM 2015 drew more than 150 postdocs, graduate students, and faculty from countries including Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, China, and the US to discuss their latest research.

Kohei Ichikawa of the Department of Astronomy, Kyoto University, shares his thoughts on what makes this meeting unique, his role as a member of the EAYAM 2015 Scientific Organizing Committee, and the importance of international collaboration.

First of all, what led to your involvement in EAYAM?

Ichikawa: I originally attended EAYAM in South Korea in 2011. This was actually my first experience of attending an international conference and I really appreciated the fact that the EAYAM Scientific Organizing Committee supported all accommodation and travel fees for graduate students. EAYAM 2011 gave me great opportunities not only to present my work but also to discuss current topics of interest internationally. Through these discussions, I made many friends in East Asia.

Subsequently, I was invited by Dr Hideaki Fujiwara of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) to join the Scientific Organizing Committee for EAYAM 2015, which is actually the fifth meeting. The first one was held in Taiwan in 2003, followed by Japan in 2006, China in 2008, and South Korea in 2011. This year, it came full circle and was held once again in Taiwan.

Kohei Ichikawa with colleagues at EAYAM 2015

In your view, what makes this meeting unique?

Ichikawa: I think EAYAM is unique in being supported by the East Asian Core Observatories Association (EACOA). The goal of EACOA is to promote dialogue and collaborations between the four big astronomical observatories in the East Asian region: NAOJ, ASIAA, the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI), and the National Astronomical Observatories of China (NAOC). The meeting really encourages graduate students and postdocs to interact informally and to spark new collaborations.

What does your role as a member of the Scientific Organizing Committee involve?

Ichikawa: I have three main roles. One is to discuss the scientific goals of EAYAM 2015 with other Scientific Organizing Committee members in the four regions to maximize international ties and future collaborations in East Asia. This time, the focus is on sharing knowledge about professional development and career paths for researchers, so we tried to include two panel discussions about topics such as work-life balance, challenges faced by postdocs, and outreach activities. The second is the reviewing process. We selected invited speakers, reviewing all of the abstracts submitted for the meeting and finalized about 60 presentations. I reviewed in the field of galaxies and black holes. The third involves organizing funds for travel and accommodation for participants from each country. This is essential in order to lower the barrier for participants -- especially for graduate students who don't have their own grants -- to attend EAYAM.

I understand you obtained your bachelor's and master's degrees in astronomy at Kyoto University. Did you always know you wanted to be an astronomer?

Ichikawa: I was quite interested in astronomy since I was in high school. Physicists can do all kinds of experiments and find clues to uncover fundamental laws. But in astronomy, we cannot do these kinds of experiments. What we can do is to observe astronomical objects that are located far away. I was curious about the process of locating astronomical objects and investigating their activities in the Universe just through the act of observation. That was my original motivation when I began studying astronomy at Kyoto University.

And you also hold a JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists. Could you please tell us more about it?

Ichikawa: There are basically two types of JSPS Research Fellowships for Young Scientists. One is for PhD students, the other is for postdocs. I received the former, as I was in the first year of my PhD at the time, and it has supported me for the past three years. Thanks to this system, I could buy a PC for my research and it gave me the freedom to explore and work with collaborators around the world and attend international conferences.

From your perspective, what is the research funding climate like for astronomy right now?

Ichikawa: At least in Japan, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science provides Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, called Kakenhi. Getting this grant is crucial for your research career. In the field of astronomy, new telescope plans involve international collaborations, including East Asian countries, on a gigantic scale. For example, the ALMA telescope located in Chile -- the largest millimeter and submillimeter telescope in the world -- has an East Asian Regional Center organized by Japan and Taiwan, and Korea will join this soon. And the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) now being constructed in Hawaii will be the most advanced ground-based optical, near-infrared, and mid-infrared observatory in the world. China and Japan are participating in this project. Considering these two examples, research funding may shift away from a single country towards an international collaboration model within the next ten years.

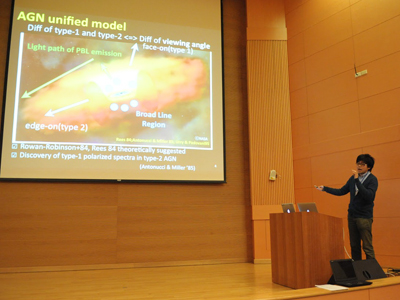

Kohei Ichikawa presenting his research at EAYAM 2015

Could you please talk us through your area of specialization?

Ichikawa: I'm tackling the issue of how supermassive black holes arise. There are tremendous numbers of galaxies in the universe, and now astronomers believe there is at least one supermassive black hole in the center of each galaxy. Even in our galaxy, in the galactic center, astronomers now know that there is one supermassive black hole with a mass about 106 times that of the Sun! But nobody knows how such supermassive black holes were formed. I've been studying active galactic nuclei (AGN), where supermassive black holes are in a rapidly evolving stage due to great mass accretion from the surrounding area. They are very bright due to the release of gravitational potential by the accretion onto the supermassive black holes. Therefore, we can observe very distant AGN from the Earth, meaning that younger supermassive black holes can be investigated through AGN.

The Subaru Telescope (left) at the top of Mauna Kea, Hawaii, is operated by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan

© Andre Nantel/Thinkstock

What kind of telescopes do you use to observe AGN?

Ichikawa: Basically AGN are very bright in all wavelengths, but two wavelength bands are especially important in understanding the growth of supermassive black holes. One is X-ray, as X-ray emission originates from the accretion disk and around the hot electron coronal region, meaning that X-ray traces the inherent AGN power. Japan's X-ray satellite Suzaku is a suitable telescope to observe such X-ray emission. The other important emission is infrared, as infrared emission originates from surrounding dusts heated by the central engine. By observing in the infrared band, we can estimate how much of the dusts, or "fuel" of AGN, are located around the central engine, and we can calculate how much of the dusts can accrete to the central engine (and finally to the supermassive black holes) in the future. Japan's Subaru telescope in Hawaii is a suitable telescope to observe those infrared bands. I generally use those telescopes as well as combining other observational data, for example, from Japan's infrared satellite AKARI, and NASA's X-ray satellite Swift.

What would be the best way to view your publications?

Ichikawa: All of our work is archived under the "astro-ph" category on arxiv.org, an open access database with e-prints in astronomy, physics, mathematics, computer science, quantitative biology, quantitative finance and statistics. It was started by Cornell University. There are mirror sites located all over the world. There's one located in Kyoto University at the Yukawa Institute for Theoretical Research. My publication list is also available from my website.

In your view, what are the advantages of conducting astronomical research at Kyoto University?

Ichikawa: There are specialists in many different fields of astronomy at Kyoto University. Owing to this, our department attracts many postdocs and researchers from other institutes. One of my collaborations actually started as a direct result of a discussion held during a visitor's stay. Chris Packham, associate professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio, visited our department and gave a talk about his group's work on supermassive black holes and MICHI (未知), one of the candidate instruments for the TMT in Hawaii, with first light planned for around 2020. I was really fascinated by his study of supermassive black holes and contacted him to join the project. After that, I stayed in Texas to collaborate with him further. Our first paper along with his collaborators in US, Chile, and Spain has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal in 2015 -- the preprint is here. Being able to collaborate is a key part of astronomy; our department at Kyoto University helps to makes this happen.

The Department of Astronomy is also planning to build a 3.8-m telescope on Okayama, which will be the largest optical-infrared telescope in Asia. This is expected to lead to new research and follow-up observations of transient objects such as supernovae and exoplanets.

Also, our department organizes stargazing events for children at Kyoto University Hospital working with a volunteer group called Oukado (黄華堂). These events are held once every fortnight or once every two months. Professor Shin Mineshige is involved in making children's books as well as Braille books that explain about the Sun or craters, which can be 'read' by touch.

The Andromeda Galaxy contains a supermassive black hole at its center

© m-gucci/Thinkstock

That sounds fascinating. In addition, I understand you are involved in public engagement projects such as Kyoto Science Sequence (KSS). Could you tell us a little more about this project?

Ichikawa: Yes. Although outreach activities have become more and more widespread in recent years, my colleagues and I realized that very rarely do these events cover cutting-edge research for high-school students who already have a great interest in science. So, we launched KSS in 2013 specifically to connect graduate students or postdocs with high school students. In addition to making communication materials aimed at high-school level, we also arrange to give talks at high schools. This is mutually beneficial because graduate students or postdocs can gain experience giving one-hour presentations and hone their communication skills, while high school students can gain insights into new research fields and think about future career paths. I was a founding member and have served as president of the KSS project since 2014.

And finally, what would be your advice to early-career researchers interested in continuing their astronomical studies at Kyoto University?

Ichikawa: Keep active! It's important to attend as many seminars in your department as possible, even if they don't necessarily relate to your main research interests, and don't hesitate to ask questions. If you come up against any hurdles, reach out and ask -- somebody may have experienced the same things. Make lots of friends by attending conferences and meetings. They will be your potential collaborators. And finally, read papers that helped to define the fundamental principles in your field. This knowledge will be indispensable in your future research and collaborations.

Thank you very much for your time.

Published: 24 February 2015

Profile

Kohei Ichikawa is a PhD candidate at the Department of Astronomy, Kyoto University. He obtained his bachelor's and master's degrees in astronomy from Kyoto University in 2010 and 2012 respectively. He received a JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists in 2012 and is a member of the Astronomical Society of Japan. Since 2014, he has served as president of Kyoto Science Sequence, a science communication group organized by graduates of Kyoto University.

Further information

- For more information about Kohei Ichikawa's research, click here

- For information about Kyoto Science Sequence, click here

- For further information about EAYAM meetings, click here

Kyoto University Research Administration Office (KURA)