Moving across borders

An interview with

Wako Asato

Program-Specific Associate Professor

Graduate School of Letters

Understanding migration for social sustainability

In December 2014, Wako Asato, Program-Specific Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University, received a Presidential Award in the Philippines in recognition of his exceptional work on migration research and related activities. Here he shares his thoughts on receiving the award, his efforts to establish scholarship grants for students in Central Visayas, and his current work with the Kyoto University Asian Studies Unit.

The medal presented to Dr Asato by Philippine President Benigno Aquino

Congratulations on your award. How do you feel about it?

Thank you very much. I think I'm probably still too young to receive this award! I view it as great encouragement for future steps. It is certainly an honor to be recognized in this way, particularly as it serves to highlight our work with the Commission on Filipinos Overseas (CFO), an agency of the government of the Philippines. I would also like to state that there are many people working to help Filipino emigrants and exploring issues associated with migration.

Could you please tell us what originally led to your work on migration issues?

I lived in the Philippines from 1997 to 1999. I go there for anthropological research, which is how I first got to know about migration issues. A great number of people move out of the country to seek jobs. There are many tragic stories such as exploitation during the process of recruitment such as underpayment, non-payment, and other kinds of human rights violations. When I started research at that time, I was astonished by a poverty-stricken elementary school girl's statement of her wish to become Japayuki (a derogatory term used to describe women who go to Japan as "entertainers"). I was very interested in the global mechanisms behind these issues.

The medal recognizes the instrumental role you have played in establishing the Bohol Japan Friendship Link and in promoting dialogue between governmental bodies in Japan and the Philippines. Could you please tell us more about this work?

The Bohol Japan Friendship Link is a scholarship program that we launched in 2000. It was set up in Bohol, an island province of the Philippines in Central Visayas. There was a Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) project for the construction of a dam. Cash income is very limited in the rural economy and students have great difficulty in pursuing their academic goals. In some cases, female students are involved in sexual activity to pay for tuition fees. By working together with some JICA specialists and my colleagues, we were able to help set up NGOs and provide scholarships to underprivileged students at some universities on the island.

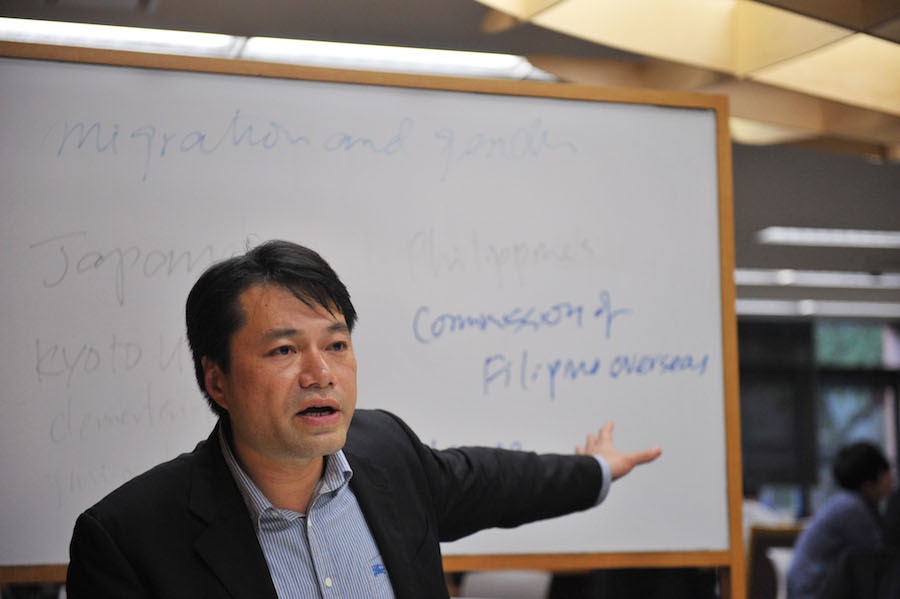

Dr Asato highlights the work of the Commission of Filipinos Overseas

Could you please tell us what these students are doing now?

Some have already finished college. The problem is that even after graduation, their futures are not guaranteed due to the undersupply of work. They often end up working abroad. These are structural issues not just at the individual level but also on a national and global scale.

Could you please describe the current situation for emigrant workers in Japan?

There are now more than 700,000 foreign workers in Japan. Regardless of their contribution to society, foreign residents often become a scapegoat -- this goes against the idea of zen'in sankagata shakai (全員参加型社会, "all participation society"), which I believe is needed to overcome issues associated with the declining population. In Japan, the three major types of discourse on foreign nationals is very interesting. One relates to security issues. The second is about social costs such as welfare. The third is labor market competition. I believe that each of these discourses can be refuted. Regarding security, if the correct integration policy is implemented, they have a more stable income source, and if they are provided with education in terms of language and occupational training and so forth, they will be less likely to commit crimes. Social inclusion policy leads to greater security.

Taking the example of nurses and care workers' movement to Japan under the Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement (JPEPA), the government provides 2.5 million yen for education per head, which has become a target of criticism. However, this is not expensive considering that they also pay tax and social security. If they pay 0.5 million yen per year and work in Japan for more than five years, this means they will pay back more than the amount invested, hence it is not about social costs. We need to pay for education but at the same time, it's about the potential. It's investment. I often collaborate with the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and my view is that the current policy does not include foreign residents. I strongly suggest that there should be an integration policy for foreign residents in order not to lead to exclusion and social problems in the future. There is a discourse of labor market competition. However, we have lost 3 million people working in the manufacturing sector in 20 years due largely to a lack of human resources. With the population decline in Japan, there's a decrease in labor market competition.

These key topics such as the rapidly aging society and low birthrate in Japan are explored in your book, Collapse of Japan Closing the Door to Foreign Workers (2011). Could you please tell us more about how society is changing and what needs to be done?

There is clearly a need to offset the declining population in Japan. The traditional male breadwinner model was successful in the 1960s and 1970s but now we need to adapt to the rapidly aging population and changing labor market demands. Regarding hundreds of thousands of spouses now living in Japan, job opportunities are very limited and their lives are difficult, even more so if they have children. Some end up receiving welfare because they have no option and are often excluded from mainstream education. This became evident during the financial crisis in 2008 and the great earthquake in 2011. The current system does not suppose that there are non-Japanese-speaking Japanese, even though there are many kinds of Japanese people living in Japan now. We must be in a position to be able to provide appropriate education.

In your view, what would be a more suitable or successful model for society if the breadwinner model, as you say, is outdated?

With the current population structure, I think that the "all participation society" is a basic requirement. The Abe administration often refers to this model, which I believe should have been implemented 20 years ago. At the same time, I think that not only economic activity but also domestic work needs to be equalized. Otherwise, basic access to participation will be hindered. We have a right to work and we have a right to care.

For students interested in pursuing migration studies, would you say that it is advisable to have a grounding in subjects such as law or economics?

Yes, I think they must have an academic backbone: Law is important because it frames the movement of people and it regulates inclusion/exclusion of people as well. Economics is also important because the economic aspect comprises a significant part of migration. Going to the field and learning from the field is very important because you can see the difference between institutional and real-world settings. Sometimes I notice students are good at reading and they are well trained in terms of answering fixed types of questions. They don't necessarily have ideas from the ground, so I'd like them to go to the field and think on their own. My students go to elementary and junior high schools to support foreign-born students, where they learn the reality of multicultural society is very different from what they learn in the textbook.

What other skills would you highlight as being important to succeed in this area?

I think communication ability is particularly important -- not just writing and speaking skills but communication in general. In Japan, there's a term known as "KY", which stands for kuuki yomenai. It's often translated as "can't read the air". One of my Indonesian friends said, "We cannot see air but we have to read the air in Japan!" Sometimes Japanese expectations are very high. This probably does not account for diverse people because other people might think in a different way. Communication skills in a global setting have nothing to do with "KY". We have to look for different kinds of communication modes.

In my class, I ask my undergraduate and graduate students to go to primary and secondary schools. They support students who cannot speak good Japanese because they migrated from the Philippines and sometimes they have difficulty in catching up with the class. There is a huge demand for Japanese language education in schools. However, education for migrant children is not well systemized. This is why I send my students and they learn a great deal. I ask them to keep a record every time they visit, which becomes an important basis for our feedback system to the Philippine government. They talk about their activities with the Philippine government so that they will know what is happening in Japan. Subsequently, they can provide appropriate comments and guidance during pre-departure orientation seminars for Filipino emigrants to Japan. I invite officers from the Commission on Filipinos Overseas who are also counselors for the pre-departure orientation seminar so that they will understand more about Japanese society and the condition of immigrants. We are doing joint research in Japan. That's actually how we discovered the human trafficking case in Osaka, which was highly publicized in 2014. This collaboration is very important.

Could you please tell us how these activities relate to your work at Kyoto University?

The volunteer activities are part of the Kyoto University Asian Studies Unit (KUASU) program. It's a wonderful program because students can do volunteer work in Kyoto City and give talks about their experiences in Manila in English, and we invite officers from the Commission to Japan, so this program has a very flexible arrangement. For some students, it would be the first time for them to present in English. Learning to give lectures seven or eight times in two weeks is a great experience.

Currently Dr Asato teaches and organizes programs including the Next-Generation Global Workshop at Kyoto University

When was the KUASU program launched?

The program was officially launched in 2012 but volunteer activities have been going on for longer. I appreciate the fact that KUASU can integrate volunteer activities into the official educational program. I consulted with KUASU Director Professor Emiko Ochiai and it became a core part of the program. Working together with Professor Ochiai, we organize workshops between East Asian universities such as Seoul National University and National Taiwan University. We also organize the Next-Generation Global Workshop, which is for masters and doctoral students from 14 countries this year. KUASU organizes many unique programs.

Now, in terms of your own journey as a researcher, what were your reasons for coming to Kyoto?

I'm originally from Okinawa, on the periphery of Japan. It used to be an independent country. I was one year old when Okinawa was returned to Japan. I was there until the age of 21, when I graduated from college. My identity is "double" -- both Japanese, and sometimes Okinawan. On this point, I may be different from other Japanese. I understand minority issues and exclusion from a historical perspective, which may evoke migration issues. This is probably what I can contribute to the academic field as well as Japanese social policy.

How is growing up in Okinawa different to growing up on the mainland?

Good question. Probably sameness and difference are defined through the process of social construction. If Okinawa was fully integrated, probably many Okinawans would identify themselves as Japanese. However, it may be that historical reasons and current political issues surrounding US bases and interpretation of Japanese history let Okinawans think we are different. Minority does not exist per se. It is constructed through politics. Migration is actually very similar because emigrants are a minority in society. Migration studies are perhaps a parallel to my own background.

Returning to the concepts of integration and assimilation, could you please explain the difference between the two?

Yes, there is a need to distinguish between integration and assimilation. Integration involves acquiring necessary skills to survive in the country like language, occupational skills, and so forth. Assimilation is more about identity -- it's more on a psychological level. This should be clearly differentiated.

In 2008, during the financial crisis, the unemployment ratio of Nikkeijin (migrants of Japanese descent) in Japan soared up to 80% in some concentrated areas such as Minokamo City, Gifu Prefecture. One of the reflections at that time was that Japanese language and occupational training is very important -- an integration policy is needed.

In addition to addressing integration, what in your view are the challenges ahead for Japan?

Those who are above the age of 65, the dankai no sedai (団塊の世代, the baby boom generation), are the ones who constructed the current economic and social basis of Japan. Their contribution is significant. At the same time, we are now experiencing the so-called "silver democracy" because the voting ratio of the younger generation is much lower, in addition to declining fertility. The redistribution of the social system has to be reviewed. However, Japan has difficulty in incorporating diversity because of the legacy of the male breadwinner model. Work-life balance also needs to be addressed. Traditionally, we work hard until we burn out. We have to get out of this vicious cycle. Otherwise, the future of Japan is very pessimistic because the traditional system cannot include diversity. This issue applies not only to Japan. The same thing could be said, for example, for other East Asian societies. Therefore, cooperation with other countries will become more and more important in the years to come.

Thank you very much for your time.

[Published: 23 January 2015]

Profile

Wako Asato obtained his PhD in Economics at Ryukoku University in 2006 and from 1997 to 1999 pursued postgraduate studies at the Asian Center of the University of the Philippines. Prior to joining Kyoto University as Program-Specific Associate Professor in October 2008, he was a Senior Research Fellow at the Sasakawa Peace Foundation. Dr Asato specializes in migration research, the empowerment and integration of migrant workers, and aging-related issues, focusing on Asian countries.

Further information

- To discover more about Dr Asato's work, click here

- For more information about the Kyoto University Asian Studies Unit, click here

- For a news story about Dr Asato receiving his 2014 Presidential Award for Filipino Individuals and Organizations Overseas, click here

- For information about The 2014 Presidential Awards for Filipino Individuals and Organizations Overseas, click here

Kyoto University Research Administration Office (KURA)