September 25, 2012

(From left) Prof. Takeshita, Program-Specific Assoc. Prof. Hirata and Researcher Sakai

The brains of humans increased dramatically after the emergence of the genus Homo. Indeed, the size of the cerebrum, in particular, is much larger in humans than in other primate species. A research team led by Researcher Tomoko Sakai (Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University), Program-Specific Associate Professor Satoshi Hirata (Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University), and Professor Hideko Takeshita (The University of Shiga Prefecture), in collaboration with the Hayashibara Great Ape Research Institute, revealed the pattern of growth in the brain volumes of chimpanzee fetuses for the first time. The results illustrated that the growth velocity of the brain volumes of chimpanzee fetuses does not accelerate during late pregnancy, whereas that of human fetuses does accelerate through late pregnancy. This indicates that humans and chimpanzees differ with respect to the development of brain volume during the fetal period and that human encephalization begins in utero. These results are reported in Current Biology, a journal published by Cell Press.

Outline

It is important to track the evolution of the brain to understand the basis of the mind and behavior of humans. Examination of the evolutionary foundation of remarkable human encephalization involves an investigation of the process by which the brain develops as well as an understanding of the morphology of the adult brain.

Since the 1950s, researchers have used post-mortem brain and/or cranial samples to compare the brains of humans with those of non-human primates to understand the developmental mechanisms that have enabled human encephalization. These studies have led to several hypotheses. The current leading hypothesis posits that the extraordinary brain enlargement observed in humans is attributable to both postnatal and prenatal development.

However, few studies have investigated the brain development of non-human primate fetuses. In particular, no information is available about brain-volume growth in the fetuses of chimpanzees, the closest living relatives of humans. Thus, our understanding of the extent to which brain development in human fetuses differs from that in non-human primates and how human brains grow during the fetal period is severely limited.

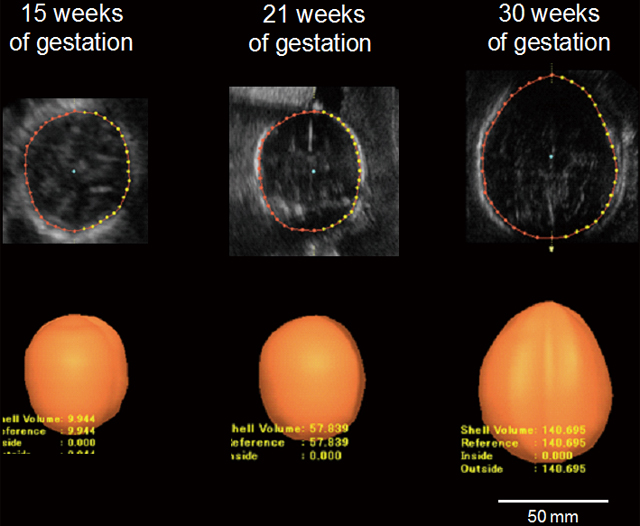

Working at Hayashibara Great Ape Research Institute, we investigated the pattern of growth in chimpanzee brains from the 14th week of gestation until just before birth using three-dimensional ultrasonography. Our observations were compared with those in human fetuses (Fig. 1, 2).

Figure 1. Scan of a chimpanzee fetus using three-dimensional ultrasonography

Scan of a mother chimpanzee named Mizuki 21 weeks after she had conceived. The mother was relaxed during the scanning and, like humans, did not require anesthesia because the researchers had established a trusting relationship with the chimpanzees since the latter were young.

Figure 2. Images of the ontogenesis of the chimpanzee fetal brain.

Three-dimensional ultrasound brain images from one chimpanzee fetus (Iroha) at 14 weeks, 21 weeks, and 30 weeks of gestation are shown. The upper row shows sonographic axial images of the brain. The lower row shows three-dimensional renderings of the brain.

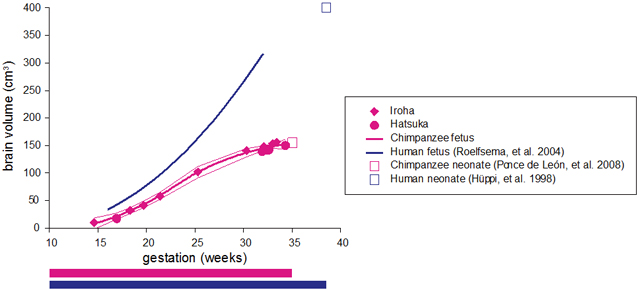

The results indicated that the brain volume of chimpanzee fetuses was half that of human fetuses at the gestational age of 16 weeks (Fig. 3). We also observed an additional difference between these species: The growth velocity of the brain volumes of human fetuses continued to accelerate until about 32 weeks of gestation. In contrast, chimpanzee fetuses exhibited a different growth pattern. Although the growth velocity of the brain volumes of both chimpanzees and humans increased until approximately 22 weeks of gestational age, after that point, the brain volume of chimpanzee fetuses did not show the continuing acceleration in growth that was observed in human fetuses. At 32 weeks of gestation, the estimated velocity of human brain growth was 26.1 cm3/week, whereas that of chimpanzee fetuses was 4.1 cm3/week (Fig. 4). In summary, unlike in human fetuses, the brain volume of chimpanzee fetuses did not show accelerated increase after the middle period of pregnancy.

Figure 3. Gestational age-related changes in brain volume in chimpanzee (Hatsuka and Iroha) and human fetuses.

The magenta solid line represents the LOESS fit of the chimpanzee fetus. The blue line represents the linear fit of the human fetus. The fine magenta lines represent the 95% confidence interval of the LOESS fit. We used data from Roelfsema, et al. (2004) for the brain volume (50th percentile) of human fetuses.

Figure 4. Gestational age-related changes in the growth velocity of brain volume in chimpanzee and human fetuses

We calculated the growth velocity of chimpanzee and human fetuses based on the LOESS fit shown in Figure 3. The magenta line represents the growth velocity of chimpanzee fetuses. The blue line represents the growth velocity of human fetuses. The color bars below the graphs represent the gestational time based on the time of conception in chimpanzees (magenta) and humans (blue).

These results indicate that human brain enlargement starts during the fetal period. Our study suggests that humans have a unique pattern of brain development characterized by acceleration in brain growth through late pregnancy. This difference is likely to be obtained in human lineage after the split of the two species following their evolution from a common ancestor. The maintenance of the rapid development of the human brain during intrauterine life has contributed to the remarkable brain enlargement observed in modern humans.

The results illuminate the evolution of humans by suggesting that uniquely human characteristics start to develop in the intrauterine environment. Our study highlights the importance of monitoring both prenatal and postnatal periods in efforts to promote the healthy growth of the minds and brains of children.

Information about the paper

Paper

[DOI] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.062

[KURENAI Access URL] http://hdl.handle.net/2433/160032

Sakai T, Hirata S, Fuwa K, Sugama K, Kusunoki K, Makishima H, Eguchi T, Yamada S, Ogihara N, Takeshita H. Fetal brain development in chimpanzees versus humans. Current biology, 22(18), R791-R792, 2012/09/25.

Corresponding authors

Tomoko Sakai (Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University), Satoshi Hirata (Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University), and Hideko Takeshita (The University of Shiga Prefecture)

This work was financially supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (# 20330154 to Hideko Takeshita and #20680015 to Satoshi Hirata) from JSPS, by a Grant for Young Scientists (#21-3916 to Tomoko Sakai) from JSPS, by the Global Center of Excellence Program of MEXT (A08 and D11 to Kyoto University), and by WISH Grant and Human Evolution Grant to the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University.