March 6, 2013

From left, Prof. Fujita, Reader Anderson and Dr. Ayaka Takimoto (University of Tokyo)

Drs. Kazuo Fujita (Professor, the Graduate School of Letters), James R. Anderson (Reader, Division of Psychology, University of Stirling, UK.), and others have found that tufted capuchin monkeys emotionally evaluate humans after observing two people interacting in ways irrelevant to the monkeys’ own benefit.

This study was published as two separate papers, one in Nature Communications and the other in Cognition.

Abstract

Humans are affective beings. They not only feel basic emotions such as happiness and sadness but also have various higher-order affects such as adoration and jealousy. Humans feel emotions even at a sight of third-party interactions that have nothing to do with themselves. How these complex affective functions have evolved has not been answered yet. In order to tackle this problem, we exposed tufted capuchin monkeys, a New World monkey species known to have a rich repertoire of facial expressions and to form a tolerant and cooperative society, to interactions between two human actors. In Study 1, one actor (the requester) asked the other (the responder) to help her/him open a container. The responder either helped or refused to help the requester. After the interaction, both actors offered food in their hand to the monkeys. The monkeys most often shunned receiving food from the uncooperative responder. In Study 2, two actors exchanged neutral items. The actors either exchanged fairly or unfairly in terms of the number of objects. When both actors offered food, the monkeys less often accepted food from the actor who had behaved unfairly to the benefit of her/himself. These results suggest that tufted capuchin monkeys form a preference between, or a kind of emotional evaluation of, the two participants based on their interactions regarding objects that are of no value to the monkeys. Thus an aspect of complex affective functions is shared in at least one non-human primate species.

Background

Humans are often labeled as affective beings. They not only feel basic emotions shared by nonhuman animals such as happiness, sadness, anger, and fear but also have various higher-order affects such as adoration, friendship, jealousy, and compassion.

It seems natural for both humans and nonhumans to feel various emotions upon experiencing events directed to themselves, such as receiving a reward or encountering danger. However, humans feel emotions even at a sight of third-party interactions that have nothing to do with themselves. For instance, we come to be favorably disposed toward a person who behaves kindly to others, whereas we feel anger or disgust when observing a person who is cruel to others.

In humans, this affective function emerges early in infancy. For instance, Vaish et al. (2010) exposed 3-year-old children to two types of interaction between two adults. In one interaction, one of the actors behaved harmfully to the other by robbing an object from the latter or by breaking it. In the other, one actor helped the other by picking up a fallen object or by fixing it. After witnessing the interaction, the children were asked to help either of the actors or a neutral person by giving a ball needed for a game. The young participants helped the harmful actor less frequently than the neutral person. Such negative evaluation may appear much earlier. Hamlin et al. (2007) exposed infants as young as 6 months old to an animation, in which one simple-shaped character helped another to climb up a hill whereas another blocked the attempt. When the infants were asked to choose among the characters, they less frequently chose the nasty character than the neutral character.

Is this kind of third-party emotional reaction unique to humans? Or, do other animals emotionally evaluate others solely through observation of interactions between agents, which have nothing to do with the animals? If so, what types of acts are they sensitive to? We conducted experiments with tufted capuchin monkeys, a New World monkey species known to have a rich repertoire of facial expression and to form a tolerant and cooperative society.

Methods and Results

Study 1

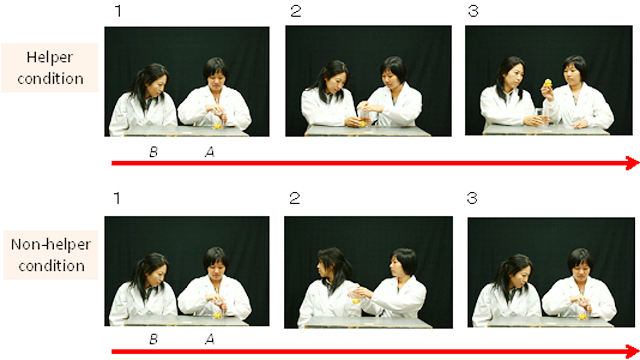

This study examined how capuchin monkeys respond to those who helped others upon request and those who rejected the request for help (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Some of the interactions of actors exposed to the monkeys in Study 1

Helper condition: (1) A tries to open the container. (2) A asks B for help. B helps A. (3) A succeeds and gets the toy.

Non-helper condition: (1) A tries to open the container. (2) A asks B for help. B rejects A’s request by looking away from A. (3) A keeps trying but does not succeed.

Occupied non-helper condition: (1) Both A and B try to open the container. (2) A asks B for help. B is focused on her own attempt and does not help A. (3) Both A and B continue trying. Neither succeeds.

Head turn condition: (1) Both A and B try to open the container. (2) A stops briefly but does not ask B for help; B also stops briefly and turns her head. (3) Both A and B resume trying. Neither succeeds.

The monkeys were exposed to the following interactions between two human actors. Actor A tries to remove the lid from a container to get a toy that is of no value to the monkeys. After attempting in vain, Actor A asks Actor B for help by showing the container held in hands. In response, Actor B either helps A (Figure 1: Helper condition) or rejects the request by looking away from A (Figure 1: Non-helper condition). After this, both actors offered the monkeys the same food in the palm of their hand by extending their arm. There was no differential consequence no matter which actor the monkeys accepted food from. In fact, when Actor B helped Actor A, the monkeys nondifferentially selected the actors. But when Actor B rejected A’s request, the monkeys less often accepted food from unhelpful Actor B. By testing various control conditions, we found that the explicit gesture to reject A’s request led to the monkeys’ shunning Actor B. Other factors such as whether Actor A finally succeeded in getting the toy, whether Actor B also manipulated the container (Figure 1: Occupied non-helper condition), and whether Actor B turn her head (Figure 1: Turning head condition) were all irrelevant.

Study 2

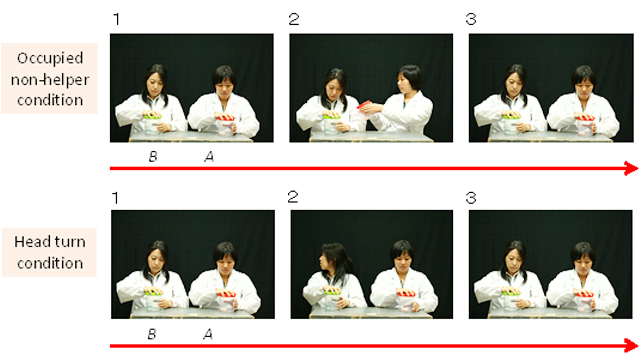

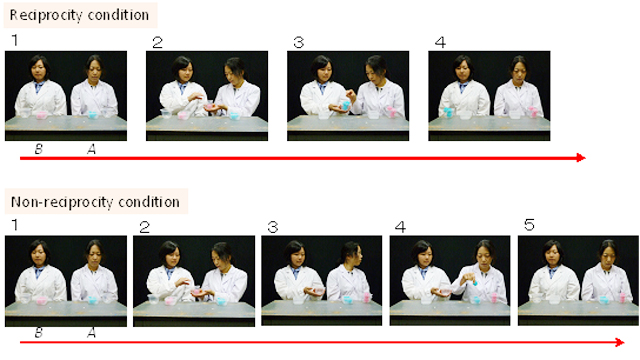

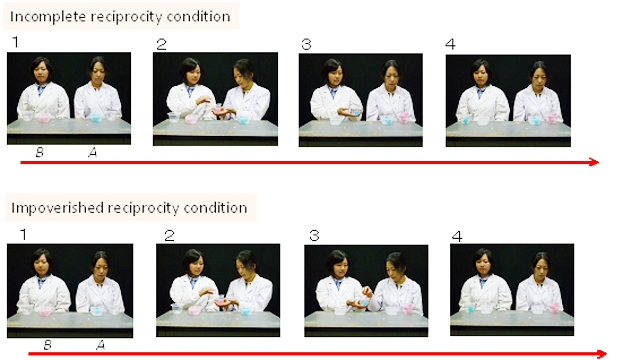

This second study examined monkeys’ response to those who reciprocate fairly in a third-party interaction and those who reciprocate unfairly (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Some of the interactions of actors exposed to the monkeys in Study 2

Reciprocity condition: (1) Initial status: each actor has 3 balls. (2) B gives all of her balls to A upon request by A. (3) B requests A’s balls in return. A gives all of her balls in response to B’s request. (4) Final status: each actor ends up with 3 balls.

Non-reciprocity condition: (1) Initial status: each actor has 3 balls. (2) B gives all of her balls to A upon request by A. (3) B requests A’s balls in return. A shows a rejecting gesture by turning away from B. (4) Then A simply picks up three balls. (5) Final status: A has 6 balls and B has none.

Incomplete reciprocity condition: (1) Initial status: each actor has 3 balls. (2) B gives all of her balls to A upon request by A. (3) B requests A’s balls in return. A gives only 1 ball to B. (4) Final status: A has 5 balls and B has 1.

Impoverished reciprocity condition: (1) Initial status: B has 3 balls whereas A has only 1. (2) B gives all of her balls to A upon request by A. (3) B requests A’s ball in return. A gives her single ball to B. (4) Final status. A has 3 balls and B has 1.

Each of the two actors had three balls, which were of no value to the monkeys. Actor A requested Actor B to give B’s balls by showing an empty container. After B gave all of the balls, Actor B requested that Actor A give balls in return. After this interaction, both actors offered the monkeys the same food in the palm of their hand by extending their arm. Just like Study 1, there was no differential consequence no matter which actor from which the monkeys accepted food. In fact, when A returned all of the 3 balls (Figure 2: Reciprocity condition), the monkeys nondifferentially selected the actors. However, the monkeys less frequently accepted food from A when A refused to reciprocate (Figure 2: Non-reciprocity condition) and when A returned just 1 ball out of 3 (Figure 2: Incomplete reciprocity condition). But, interestingly, the monkeys’ choice of actors was indifferent when Actor A had only 1 ball from the beginning and returned this sole item upon B’s request (Figure 2: Impoverished reciprocity condition).

These two studies suggest that tufted capuchin monkeys attend to third-party interactions, form a preference for, or an emotional evaluation of, the persons involved, and modify their behavior towards these participants.

Previous studies reported that chimpanzees would stay close to a person who generously gave food to others and that they learned to request food from generous human givers. These are clearly responses to their own benefit. In the present studies, human interactions always involved items that were of no value to the monkeys. Thus the monkeys’ behavior does not seem to be a simple response to their own benefit. Further, because the monkeys collected exactly the same food irrespective of their choice of actors, there was no chance to learn to choose one actor over the other in terms of food reward. Therefore this behavior of our monkeys does not appear to be a rational decision but a decision based on their emotional states. In conclusion, tufted capuchin monkeys appear to share with humans an affective function to emotionally evaluate others based on third-party interactions.

Ripple effects

First, the present studies provide highly important new material for discussing human nature. Emotional evaluation of others based on third-party interactions irrelevant to themselves is now shown not to be unique to humans. This additional evidence for continuity of human and nonhuman minds calls for further revision of the concept “human.” Also, the present evidence affirms that a popular view of “ever-ascending evolution toward humans” is incorrect, as capuchin monkeys are phyletically much farther from humans than great apes; capuchins’ ancestors diverged from their Old World counterparts more than 35 million years ago.

Second, the present studies shed new light on the evolution of humans’ amazingly cooperative society. Our cooperative society is supposed to be maintained by “indirect reciprocity” based on the formation of “reputation.” The present studies showed that third-party evaluation, which constitutes the first step in forming “reputation,” is shared with at least some nonhuman animals. This implies that the cooperative society of humans may not have developed abruptly in the human lineage, but that it may have a surprisingly old origin.

Third, the monkeys’ shunning actors who explicitly showed a rejection gesture in Study 1 indicates that capuchin monkeys may be sensitive to others’ intention. Understanding of others’ mental states has not been well documented in monkeys. The present studies imply that rudimental form of such mind-reading ability may be shared among more diverse animals than has been thought.

Future plans

What we have shown in capuchin monkeys is a dislike of the third-party who shows selfish and unfair acts such as rejecting requests for help or not reciprocating in exchanges with others. This resembles the behavior of young children and infants and thus may suggest a homologous relationship between the behavior of capuchins and humans. However, human adults also feel positive emotions for people who behave fairly and kindly to others. A next question of ours is to examine whether such positive behavioral change also occurs in capuchin monkeys. If the answer is yes, the third-party evaluation by capuchin monkeys is more likely to be homologous to that in humans. Such homology would provide even stronger evidence for continuity of human and nonhuman minds.

In order for this third-party evaluation to actually function and translate into a cooperative society such as that of humans, agents have to adjust or modify their behaviors by caring about such evaluation. Thus another question is whether monkeys would behave differently in the presence of social others than alone. At the same time, how widespread such social evaluation is in the animal kingdom should also be explored.

The experiments were conducted in a project aiming to understand evolution and development of cognitive meta-processes, or active access to own mental states, often labeled awareness or self-reflection, by phylogenetic and ontogenetic comparisons, and to unveil how these meta-processes relate to mind-reading. We will keep going to unravel how the ability to understand others has evolved, how it develops, and what mechanisms are involved.

This series of studies was supported by a JSPS Grant-in-Aide for Scientific Research (S), “Awareness, self-reflection, and mind-reading: Genesis and functions of cognitive meta-processes.” (20220004) to Kazuo Fujita.

Glossary

Tufted capuchin monkeys

The tufted capuchin monkey (Cebus apella) is a New World monkey, or platyrrhine, species living in a wide area with Amazonian basin at the center of its distribution. They form multi-male groups like Japanese macaques and chimpanzees. They have a rich repertoire of facial expressions and are socially very tolerant. They often allow conspecifics to share food in their possession and sometimes even actively hand food to others. They have been experimentally shown to choose to give good food to a low-ranking individual, and also to reward others for their help with good food. This species is also known as a champion tool user among non-ape primates both in the laboratory and in the wild. They crack open hard nuts using stone hammers and anvils. Manual dexterity and learning ability are both extraordinary. These characteristics were the reasons they were selected to be trained as helpers for quadriplegic people in North America.

Indirect reciprocity

Human society is characterized by widespread cooperation. Cooperation often leads to mutual benefit to participants but at other times it can be simply a cost to helpers. It is a big evolutionary puzzle why humans became this cooperative species. Indirect reciprocity is a mechanism proposed by Nowak and Sigmund (1998) in evolutionary biology. This mechanism is most well understood by a proverb “nasake wa hito no tame narazu (what comes around goes around).” That is, cooperation enhances the reputation of the cooperator, who will in turn receive benefit at a later date. In order for this mechanism to work, monitoring and evaluating third-party behaviors by group members are needed as the first step.

Paper Information

Study 1

Anderson, J. R., Kuroshima, H., Takimoto, A., & Fujita, K. (2013). Third-party social evaluation of humans by monkeys. Nature Communications 4, Article number: 1561 (2013)

[DOI] http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2495

Study 2

Anderson, J. R., Takimoto, A., Kuroshima, H., & Fujita, K. (2013). Capuchin monkeys judge third-party reciprocity. Cognition, 127(1), 140-146 (2013)

[DOI] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2012.12.007