Research continuum

Backstage at the lab

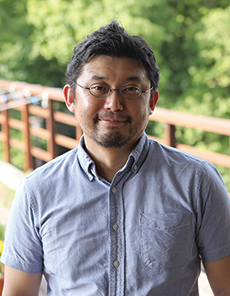

Earth, sky, space, and everything in between

A comprehensive science connecting the spheres

RISH is steeped in the culture of interdisciplinary collaboration that defines Kyoto University. Since its start on the Uji campus in 2004, the “Research Institute for Sustainable Humanosphere” has fostered many collaborative opportunities worldwide, expanding humanosphere science. The newest of these, the Humanosphere Asia Research Node or ARN, founded in 2016, strengthens hub functions for collaborative research to find solutions to environmental problems facing all of humanity. We spoke with RISH director Takashi Watanabe and top ARN-affiliated researchers to hear their perspectives and hopes for the program.

Takashi Watanabe Director, Research Institute for Sustainable Humanosphere Professor, Laboratory of Biomass Conversion

Takashi Watanabe Director, Research Institute for Sustainable Humanosphere Professor, Laboratory of Biomass Conversion Hiroyuki Hashiguchi Associate Professor, Laboratory of Radar Atmospheric Science

Hiroyuki Hashiguchi Associate Professor, Laboratory of Radar Atmospheric Science Akihisa Kitamori Assistant Professor, Laboratory of Structural Function

Akihisa Kitamori Assistant Professor, Laboratory of Structural Function Chin-Cheng “Scotty” Yang Junior Associate Professor, Laboratory of Ecosystem Management and Conservation Ecology

Chin-Cheng “Scotty” Yang Junior Associate Professor, Laboratory of Ecosystem Management and Conservation Ecology

An humanosphere research node for Asia

So, what is the “humanosphere”?

RISH identifies numerous spheres that support and interact with human activities. Institute director Watanabe explains that humanity today faces a rapid increase in problems in the world, including: population growth, global warming, shortages of energy, scarcity of raw materials, the spread of pathogens, and environmental pollution. These have disastrous implications for current and future life on this planet. To better understand these challenges, the joint efforts of scientists from multiple disciplines is a necessity.

So the humanosphere is the totality of environments encompassing human existence.

Watanabe points out that, for example through studies of the atmosphere, we can understand the global environment and how it changes. But that gets us only partway to a solution. Sustainable energy sources then need to be designed in a way to mitigate problems that have been found. Furthermore, to maintain sustainability, more ecologically friendly materials must be developed.

“RISH provides an environment aiding collaboration for both veteran scientists and new, bright-eyed researchers alike.”

The humanosphere envelopes all of humanity, requiring international cooperation to sustain the future. To that end, RISH founded the “Humanosphere Asia Research Node (ARN)” in 2016 to strengthen international collaboration and encourage humanosphere researchers to find global-scale solutions. With a new, joint laboratory and satellite office in the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, LIPI, ARN has been designed to make Kyoto University the hub of humanosphere research in Southeast Asia and the world.

“As the program develops, we seek to encourage a new generation of humanosphere researchers. Expanding an international community of scholars will be the only sure way to solve the ecological problems facing humanity as a whole.”

Atmospheric radar collaborations

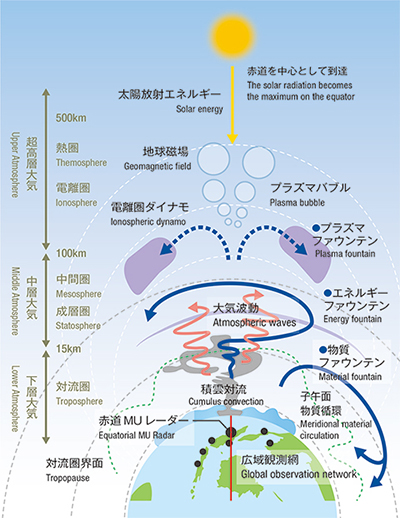

The “equatorial fountain”, to be observed by the

planned Equatorial MU radar in West Sumatra

The “equatorial fountain”, to be observed by the

planned Equatorial MU radar in West SumatraARN as a program is composed of three pillars: study of the ‘equatorial fountain’, utilization of tropical biomass, and cooperation using a humanosphere database.

Before the program’s founding, RISH already had strong ties with Indonesia in the study of the atmosphere, a bond that has existed for nearly 30 years.

“In 2001, we completed the Equatorial Atmosphere Radar, EAR, on Sumatra, and it has been running near continuously ever since,” explains chief radar scientist Hiroyuki Hashiguchi. “In light of this long history of cooperation, equatorial fountain research was designated as one of ARN’s flagship projects.”

The facility has become a symbol of collaboration with the scientific community in Indonesia. One key organization to join with RISH was the Indonesian government’s space agency, LAPAN. The two have continued to build strong connections,and have jointly held workshops to train students and researchers on how to use the radar. They are hoping that, with the implementation of ARN, interest in the radar in the atmospheric sciences will increase.

Along with workshops, ARN has organized numerous seminars and lectures to smoothly transfer information. Open seminars take place twice a month, where ARN researchers present their work over a live stream connecting RISH, LIPI, and LAPAN.

“These meetings are a bit of a challenge, because the scientists must present their data in a way that colleagues outside of their fields can understand each other’s research,” says Hashiguchi. “It is a good experience for both participants and lecturers.”

Last year, ARN held an “International Premeeting of Humanosphere Asia Research Node on Biomass Utilization”, jointly with JASTIP, the Kyoto University-led and Japanese government-funded project for promoting science with ASEAN countries. In November 2016, the Humanosphere Science School and the 6th International Symposium of Sustainable Humanosphere were held in Bogor, Indonesia. Then in January 2017, another JASTIP workshop took place, the first to be organized by ARN.

The first ARN symposium followed in February in Penang, Malaysia, which was a perfect opportunity for students and young researchers to interact.

“If you walked around the seminar hall you could see people from differing disciplines engaged in passionate discussions,” remarks Hashiguchi. “And I am happy to say that the number of participants for the 2nd ARN symposium in July was twice the number of the 1st.”

And plans are underway for an even bigger radar: the equatorial Middle and Upper atmosphere (MU) radar, ten times more sensitive than EAR and to be built just to its north. To support this, ARN’s atmospheric science program is recruiting doctoral students and postdocs to spend extended periods in ARN labs to strengthen collaborative bonds, an attractive prospect that has so far only had a few takers, likely given the project’s newness.

“EAR has been a centerpiece of the collaboration between Kyoto U and Southeast Asia, and we hope that with ARN, more people will use our facilities to pursue their research,” continues Hashiguchi. “Many Western scientists have expressed interest but don’t know whom to turn to. That’s where we come in. And we also want to increase involvement from the Indonesian academic community as well.”

While challenges remain, Hashiguchi hopes that ARN can act as a conduit for interdisciplinary communication. Through regular workshops and seminars, he aims to explore new research realms and further bridge the institute’s departments.

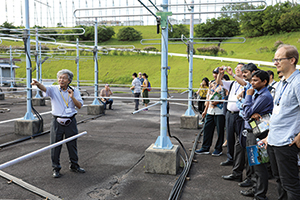

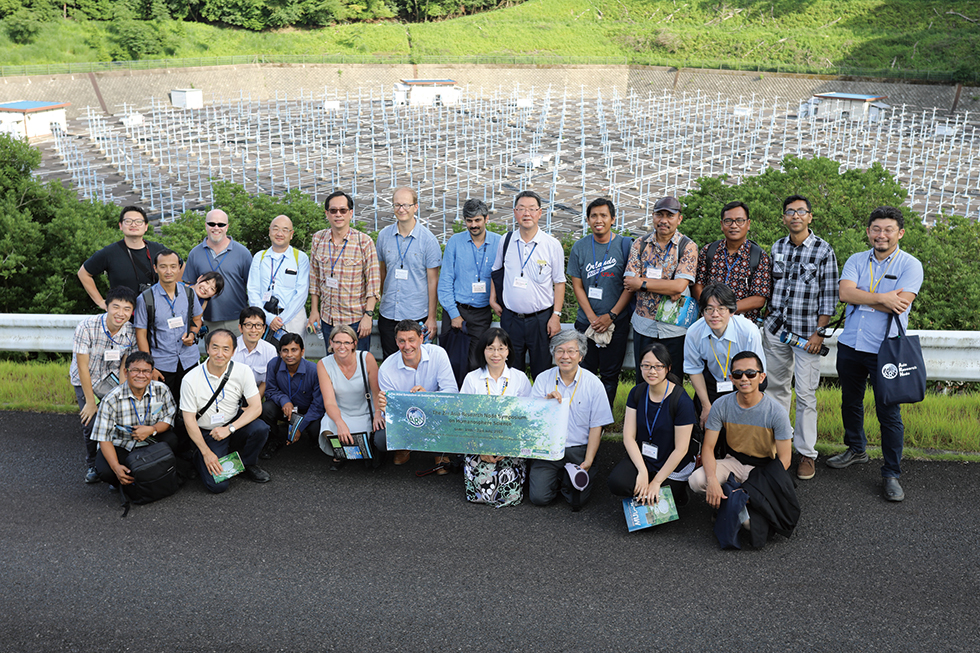

2nd ARN Symposium attendees touring RISH’s Shigaraki MU Observatory in Shiga prefecture (July 2017)

2nd ARN Symposium attendees touring RISH’s Shigaraki MU Observatory in Shiga prefecture (July 2017)Woodworking traditions into the future

Traditional architecture of the Karo region in North Sumatra

Traditional architecture of the Karo region in North SumatraWood and wood material research have a long history at Kyoto University. The Wood Research Institute, WRI, was established in 1949 and later became one of RISH’s first departments. It is appropriate that this field is also a core function of ARN.

Akihisa Kitamori focuses on the development and utilization of wood and traditional architecture in modern structures. Kyoto, of course, is renowned for its multitude of sturdy, adaptable, and beautiful wooden buildings, the most traditional of which were built with wooden joinery and few metal connectors, increasing their tolerance to Japan’s humid climate and typhoon- and earthquake-prone environment. By studying traditional architecture, Kitamori seeks to utilize such techniques in modern buildings to increase resilience and reduce cost.

But Japan is not the only country with a long tradition of wooden structures. In Indonesia, wood-based building traditions are equally well-established, but with dramatically different characteristics. This has led to extensive collaboration between the two countries, even before ARN got started.

“Since our two countries face similar natural disasters, one study I am leading seeks to understand if Japanese techniques can work in Indonesia,” explains Kitamori. “With ARN, one of our collaborative projects has focused on research and development of affordable housing, combining our traditions with new, affordable materials.”

This joint endeavor resulted in boards made from agricultural waste, such as corn and grain stalks. The project hopes to mitigate the costs in time and environmental degradation that result from traditional wood lumber use.

While the focus for these new materials will be on city housing and urban locations, research into traditional architecture centers on rural and remote locations. “In rural Indonesia, it can be extremely difficult to transport materials for affordable, modern housing. Knowing how to build without nails or modern supplies is vital for remote areas.”

Despite the newness of ARN-sponsored efforts, preliminary tests with the boards have shown success, and the building of a prototype structure is next. Reliance on ARN’s well-equipped joint research facilities at LIPI will be a cornerstone of this work.

“ARN is a program with phenomenal potential. Who knows what we will find next in our collaboration? We may discover new techniques and technologies that we can incorporate into buildings in Japan,” says Kitamori.

unsplash.com/@joshuanewton

unsplash.com/@joshuanewton

Sustainable building material made from corn and grain stalks

Crawling with Ant-icipation

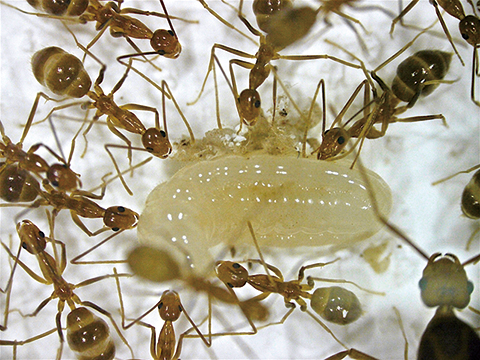

Yang’s research includes study of the invasive “yellow crazy ant”

Yang’s research includes study of the invasive “yellow crazy ant”Before Scotty Yang moved to Kyoto, he was at National Taiwan University in Taipei. His first reaction to an offer from RISH was hesitation: he didn’t know Japanese, and was unfamiliar with the research community here. But after looking into it more and hearing about ARN, he realized that the potential resources available to him would make for a great opportunity.

Yang’s contributions to the study of ‘yellow crazy ants’ — an invasive species in much of the world — are another example of ARN at work. While this species most likely stems from Southeast Asia, no one knows its exact point of origin.

Using ARN to tackle this question, Yang has enlisted the help of fellow academics and even members of the public residing in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore.

“The beauty of this collaboration is that we can avoid risks associated with invasive species,” he explains. “Since we cannot bring the ants into mainland Japan, in-country, satellite sites are absolutely vital to the research.”

Yang has been collaborating with institutes in Southeast Asia by sharing his protocols and visiting these hubs himself. Most of this joint work has been conducted at USM in Penang, but starting in 2017 he will be doing more at LIPI in Indonesia.

Another aspect of his research is finding biological control agents for the ants. Such study involves an enormous amount of work in the field, using bioassays and laboratory manipulation. So again, live ants and local labs are needed to find answers.

To facilitate cooperation, Yang holds workshops for research colleagues in the region, through which he has gained access to local citizen science networks. This has expanded his scope even further.

“I think this is a perfect example of how ARN is building a network of humanosphere science,” says Yang. “Not everyone is a trained scientist. But they are just as passionate about the research, and having them involved and building bonds of science is a sure way to get very valuable data.”

Yang sees the future of ARN as not just a research network for Kyoto University and Southeast Asian institutes, but as a hub that connects Southeast Asia to the world.

“Many institutes in the West and even in other parts of Asia want to collaborate with the academic community in Southeast Asia, but they don’t know where to start. We can help show them the way.”

ARN is next planning a short-term exchange program for students and researchers that will surely bring about even closer contacts. The more the network of collaboration grows, the better it is for science and society.

“Building a strong student community between institutes is very important to strengthen our bonds,” adds Yang. “I hope that as ARN grows, more institutes will come into the fold.”

Looking forward with ARN

Kyoto University’s mission statement includes the line, “…educate outstanding and humane researchers and specialists, who will contribute responsibly to the world’s human and ecological community.”

RISH and ARN strive for exactly that. The world is complex and intertwined, and where humans can live is limited. To improve our understanding of the earth’s ecology, a scientist working alone in a lab is not enough. From weather problems to new biofuels; animal ecology to wood materials; the oceans to space: a multi-pronged and international approach is necessary to solve the problems we face together.

RISH already understood the necessity of international collaboration when it was founded. Now with ARN, these bonds can be strengthened by training a new generation of scientists and supporting new and ongoing projects between participating countries.

This work has only just begun. Continues RISH director Watanabe, “ARN is not merely a symbolic project intended to ‘internationalize’ an institute; we are building a community to produce good science for the world. ARN’s three pillars aim at nothing less than to reinvent society.”