Japan and the West in Meiji Art

Inspiration from Joint Research

It has been five years now since I began my position at Kyoto University's Institute for Research in Humanities. My position here has given me extensive opportunities to participate in research with academics specializing in other fields and thus I have on many occasions encountered new concepts, which I feel has steadily broadened my perspective. My specialization is the History of Early Modern Art, with a particular interest in fine art of the Meiji period. Soon after I started working here, I participated in two joint research teams; one for Suguru Sasaki's "Society and Information during the Meiji Restoration" and the other for Shinichi Yamamuro's "Various Aspects of Intercultural Activities and the People Involved."

Shinichi Yamamuro's line of thought that "cultural boundaries do not exist at first, but rather can only begin to exist when different culture is encountered" was an eye-opener and tremendous inspiration for me. I then participated as a member in more joint research teams such as "research of cultural exchange between Japan and France", "the body in the early modern period", "representation and expression of race" and "research of early modern Kyoto", all of which overlapped with my interests and were golden opportunities for me to ponder on the relationship between fine art and various fields such as history, anthropology, literature and area studies.

From Impressionism to Meiji Japan

Originally, my specialization was the history of 19th century Western art. It was when I was researching neoclassicist Ingres and the impressionist Degas, that I began to develop an interest in Japanese fine art of the same period. Up until twenty years ago in the field of Japanese art history, the art of the Meiji period was not regarded noteworthy nor was it considered a subject of research. Then beginning from the 1980s, people began revisiting the period; academic societies were established, the tales of descendents were recorded while they were still in good health, works and materials were sorted, and concerted effort was made to fire up passion for the study of Meiji art. Gradually membership of these academic societies grew, academic societies published bulletins and painters who till then were unknown began to be unearthed. It was through this that I happened to view an exhibition in 1993 of a painter by the name of Hosui Yamamoto where I was shocked by such strange paintings. At the time I was overwhelmed by the element of the grotesque and sense of weirdness of these paintings (see Urashima Figure 1 and Junishi Figure 2), which are of Japanese subject matter but painted completely in Western oil painting technique. But at the same time, I felt the impact of having discovered a Japanese-style oil painting for the first time and with my curiosity piqued, I wanted to find out more about them.

Figure 2 Hosui Yamamoto "Mi (snake)" of "Junishi (Chinese horoscope)" 1892 Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Nagasaki Shipyard and Machinery Works

Hosui Yamamoto was a Western-style painter who lived in France for about 10 years in the 1870s and 1880s but there had been little research on his life while abroad. I went to Paris to do some investigation and I discovered a whole range of new things about him. Hosui had mingled closely with Parisian artists and intellectuals and he did not simply study the West. Hosui painted Japanese style decorative wall paintings, and drew pictures for an anthology of Japanese tanka poetry translated into French and as an artist exposing Japanese art, he played not a small role in the permeation of the Western Japonism movement and Japanese artistic concepts in general.

My research into Hosui was a trigger to compile a history of the reception and exchange of Western art and Meiji art, which is published as "Ikai no umi: Hosui, Seiki, Tenshin ni okeru seiyou (The Sea Beyond Hosui, Seiki, Tenshin and the West)" (Miyoshi Kikaku, 2000).

Problem Awareness of Seiki Kuroda and Tenshin Okakura

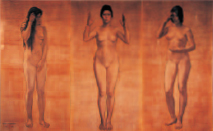

The triggers for my research are always encounters with works of art and the case of Seiki Kuroda was no exception. This time around it was the painting "Chi kan jo" (Figure 3), which was exhibited at the Universal Exposition held in Paris in 1900. This influential work portrays three female nudes in almost life size proportion with powerful effect, but despite this, the artist said next to nothing about this painting and so it is a work of mystery. I discovered some comments regarding "Chi kan jo" made by Tenshin in his personal notes and when I researched the relationship between the two artists, I found that they met each other on numerous occasions at the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko (Tokyo Fine Arts School) where they both were teaching. Moreover the two seemed to share a similar problem awareness regarding how to strategically exhibit Japan to the world at international events such as the Universal Exposition held in Paris. With Tenshin belonging to the genre of Japanese-style painting and Kuroda to the Western painting genre, researchers who focus on one genre rarely considered the link between the two artists. However people with consciousness during the Meiji period looked hard at how technology acquired from the West was fused with Japanese elements and painstakingly thought of the best ways to exhibit this internationally.

Figure 3 Seiki Kuroda "Chi kan jo (wisdom, impression, sentiment)" 1897 National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo

Research into Themes of Mythology and Legend in Meiji Art

Although Hosui's period abroad coincided with the impressionist period, his focus of study was art of the academism style, which was the orthodox style of the time. The themes of mainstream Western art were mythology and history such as Jacques-Louis David's Coronation of Napoleon and are large works that feature many people. Hosui learnt this style of painting and once he returned to Japan, not only did Japan society ban the painting of nudes, the Japanese public had no knowledge of the subject matter from the Bible or Greek mythology. He thus faced the dilemma of how to express and utilize his acquired oil painting techniques in Japan. In Western painting, the depiction of history and mythology and the expression of the nude body are inseparable. Even for paintings featuring only clothed people, many drafts of these figures in the nude would first be drawn and then the clothing would be overlaid. Thus the expression of nudes was fundamental to the expression of people.

For example, not just Hosui, but also many artists of various genres such as Kinkichiro Honda, Kiyoo Kawamura, Eisaku Wada, Japanese-style painter Seiho Takeuchi and architectural historian Chuta Ito used heavenly maidens as the themes of their work. This was partly because it easily tied in with traditional tales and religious themes such as robes of feathers, the tale of the bamboo cutter, and scattering flowers, but it is also thought to be a good theme for portraying images of the female nude. I am very interested in how Japan adopted the traditional elements of Western painting that were the most difficult to adopt, which are historical paintings and nude paintings. To explore this area more deeply I am going to focus on the themes and representation of mythology and legend of the Meiji period, particularly the portrayal of heavenly maidens in my study of the encounters of historical paintings and nude paintings in Japan.

Probing into Attempts to Fuse the West with Japan

Seiki Kuroda who studied in Paris a short time after Hosui was also faced with the dilemma of how to express in Japan the techniques he learned in the West. In 1895, Seiki exhibited a complete female nude in front of a mirror, which created a tremendous scandal. It is well known that following this incident, Seiki became depressed that the use of nudes in paintings was yet to be understood in Japan. Meanwhile in the West, the impressionist period was bringing about a demise in the tradition of nude painting and historical painting. Seiki was abroad right at the verge of this transition and so was faced with a dilemma of whether it was meaningful to import and start off a tradition that is fading in the West, or while having fully been immersed in the tradition, whether it was worthwhile to just take the radical elements of impressionism and implant them in Japan despite the fact that impressionism had emerged out of historical necessity. In the end, after much arduous decision making Seiki adopted aspects of the impressionist style that were suited to Japanese tastes (Figure 4) and followed a career in teaching at art school.

So in this way the problem of the historical painting and the nude painting was the quintessential problem of importing orthodox Western art to Japan. This would have been a serious issue not just for Western paintings but also for Japanesestyle painting where artists were attempting to create a new tradition of Japanese art by using Western technology. Since the Meiji period, up until present Japanese artists active in an international arena have created works by absorbing technologies from the West while consciously using various Japanese elements in their creation. This trend continues today in works for popular arts such as the animated film "Spirited Away". To gain a deeper perception of the trends in how Japanese culture is exposed internationally, I would also like to further research the aspect of the middle period of Meiji art that can be called the "third path", which extends beyond the framework of Japanese paintings and Western paintings, and revise the history of art in the early modern period.

Erika Takashina

Field of Specialization: 19th Century European and Japanese Art History, Relations between Japan and the West in Modern Art Completed Doctoral Degree, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, the University of Tokyo Associate Professor, Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University

I would like to continue my discussion of art history by focusing solely on individual living works, but not just in terms of the history of art; rather, I want to explore the nature of one culture where the art is closely interconnected with the literature, music and the historical context.

Dr. Takashina has spent considerable parts of her life, including her childhood years living in Europe, such as France, and through visiting art museums, churches and the like, she had countless encounters with Western art. She recalls fondly the intellectual stimulation akin to having solved a riddle when her father would explain the symbolism behind the figures and objects in a painting and provide her with some background regarding the time in which the picture was painted. This was perhaps the starting point of her current research activities in art.

Just as she herself experienced such fortunate encounters with art, Dr. Takashina approaches her research work in Japanese art of the Meiji period with a wish to increase the opportunities for students and the general public to have similar joyful encounters with art. Dr. Takashina explained that works of art are alive. But in order for an artwork to have life, it needs the people living in the current period. For it is the act of people viewing the works of art that provides the opportunity for art to influence the hearts and minds of the people, and it is this that enables the art to stay alive. Researchers and critics of art are sometimes viewed upon with lesser reverence than the artists who produced the works, but Dr. T a k a s h i n a ' s pride in her work reminds us of their invaluable role of keeping works of art alive through the ages.